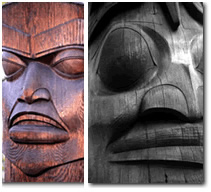

Totem Poles of Alaska

Early totem poles were like billboards

The totem pole is the most well known type of art made by Alaska Natives. No Alaska vacation is complete without seeing a few totem poles. Since they were first noticed by European explorers in the 1700s, totem poles may have been misunderstood. Britain’s Captain James Cook, who encountered totem poles off the coast of British Columbia, called them “truly monstrous figures.” Early missionaries thought the totem poles were worshiped as gods and encouraged them to be burned. And even today, when someone refers to the “low man on the totem pole,” they may not realize that the bottom figure was often the most important one – and usually, it wasn’t a man.

World famous Tlingit carver Nathan Jackson (the most famous carver in the world) works at the Saxman Carving Shed in Saxman, 2.8 miles south of Ketchikan. You can see him work there most days during the summer.

Totem Poles as Billboards?

Early totem poles were like billboards for rich and powerful native families, telling stories about the family and the rights and privileges it enjoyed. With early traders came more wealth, and more poles, some accounts talk about 19th-century native villages with hundreds of totem poles, each one shouting out the power and wealth of the family behind it.

History of Totem Poles:

From Wikipedia: Totem poles serve as important illustrations of family lineage and the cultural heritage of native peoples who live in the islands and coastal areas of North America’s Pacific Northwest, especially British Columbia, Canada, and coastal areas of Washington and southeastern Alaska in the United States. Makers of these poles include the Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl), Bella Coola, and Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka). Totem poles are typically carved from the highly rot-resistant trunks of Thuja plicata trees (popularly known as giant cedar or western red cedar), which eventually decay in the moist, rainy climate of the coastal Pacific Northwest. Because of the region’s climate and the nature of the materials used to make the poles, few examples carved before 1900 remain. Noteworthy examples, some dating as far back as 1880, include those at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria and the Museum of Anthropology at UBC in Vancouver.

Totem poles are the largest, but not the only objects that coastal Pacific Northwest natives use to depict family legends, animals, people, or historical events. The freestanding poles seen by the region’s first European explorers were likely preceded by a long history of decorative carving. Stylistic features of these poles were borrowed from smaller prototypes, or from the interior support posts of house beams. Although eighteenth-century accounts of European explorers traveling along the coast indicate that decorated interior and exterior house posts existed prior to 1800, the posts were smaller and fewer in number than in subsequent decades. Prior to the nineteenth century, the lack of efficient carving tools, along with sufficient wealth and leisure time to devote to the craft, delayed the development of elaborately carved, freestanding poles. Before iron and steel arrived in the area, natives used crude tools made of stone, shells, or beaver teeth for carving. The process was slow and laborious; axes were unknown. By the late eighteenth century, the use of metal cutting tools enabled more complex carvings and increased production of totem poles. The tall monumental poles appearing in front of native homes in coastal villages probably did not appear until after the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Where to See Totem Poles:

You’ll find totem poles all over Southwest Alaska, with at least a few in almost every town you visit.

The greatest concentrations for visitors to see are in Sitka and Ketchikan:

• Sitka National Historic Park , Sitka: Highlights here include a walk through the woods and some very old totem poles, kept inside to preserve them.

• Totem Heritage Center, Downtown Ketchikan: Great place to see the old totems.

The Totem Heritage Center was established in 1976 to preserve endangered 19th century totem poles retrieved from uninhabited Tlingit and Haida village sites near Ketchikan

• Totem Bight State Historic Park – Ketchikan: Fourteen totem poles are preserved in the park within an easy walk of the cruise ship docks.

• Saxman Village, Ketchikan: Two miles south from Ketchikan, is Saxman Village and the largest collection of totem poles in the world. Native art and culture flourishes here due to the large population of Native Alaskans. The indigenous Pacific Northwest Indian tribes are the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian. Gaze at the many massive totem poles, timeless monuments in cedar from the first Alaskans.

Types of Totem Poles:

- Crest Totem Poles: Usually part of a house, they portray a family’s ancestry and the emblems of its clan.

- Story-telling Totem Poles: The most common type, these are made for a wedding, to preserve history or to ridicule bad debtors.

- Mortuary Totem Poles: These totem poles are made to honor the dead. Cremation ashes are often kept in a compartment in the back. A single figure represents the deceased person or their clan.

World famous Tlingit carver Nathan Jackson:

Jackson began carving nearly 40 years ago, during a serious illness. “One day I was disk-sanding the bottom of a fishing boat and some of the jellyfish powder and copper paint got into my lungs. I started coughing up blood. I ended up in the hospital for 55 days. While I was there I carved several miniature totem poles.”

“Depending on how well the artist understands the art, it’s okay to experiment. But it’s best to stay within the limits of the art form so that you’re not producing something foreign. The art relates to peoples’ identities. Being Tlingit, I try not to do something that’s Kwakiutl, or something that’s from a different area.” — Nathan Jackson

Jackson, Master Carver and a Chilkoot Tlingit, has been working in Alaska Native arts since 1959. He attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he specialized in fabric design, silkscreen, and graphics. Since 1967, he has been a freelance artist doing traditional style woodcarving, jewelry, and design. Nathan Jackson has completed numerous totem poles, screens, panels, and restoration projects. He has instructed woodcarving and design at several institutions, including the Alaska State Museum, Sheldon Jackson College, the Totem Heritage Center, and the University of Alaska.

Jackson’s artwork is on display in every major museum – as well as many public and private buildings – in the state of Alaska. His work can also be found in museums and private collections throughout North America and in museums throughout Europe and Japan. Jackson was heavily involved in the Totem Park and tribal house in Saxman. (Background information about Nathan Jackson courtesy the Southeast Alaska Discovery Center – Ketchikan, Alaska.)

your awesome nathan jackson

Good afternoon,

I bought this Totem Pole at a yard sale and was wondering if you could give me any information on it. I have been to Alaska and wanted to bring one home but couldn’t. I was told this one is made in honor of Chief Johnson. Thank you very much and have a nice day!

Regards

Kelly Fowler

you have nice totem poles. And I hope we had some were i live

I am interested in a large totem, not a toy. When I was in Alaska, I fell in love with them and always wanted one. Is that possible? Thanks,

I don’t know of anyone that sells them online. I’m sure there are, I just don’t know of them. Depending upon your budget, Nathan Jackson takes commissions for his poles. And so does Donald Varnell. He makes some incredible poles. Donald is at https://www.facebook.com/donald.varnell.

What is pricing for a totem pole from Ketchikan? Anywhere from 1 foot to 4 foot y’all?

$10 to $5000 depending upon quality.

My daughter is researching Alaskan totem poles for her Daisy Troop state fair project. Could you offer up good resources for the meaning behind the different animals and figures used in totem pole carving? Thank you for help on this if you can.

Don’t know any off hand but Wikipedia would be a good start.

these totems poles are amazing

I inherited a totem pole bought in 1963. In Juneau at the nugget shop. It is 48 inches tall with an eagle on top and the soldier on the bottom. The back has the shops seal on it and the number 15 written on the back. What can you tell me about this totem pole?

Can you tell me what a totem might look like that would be placed on a rock just offshore in the harbor of Pelican, AK. I believe it is considered Tlingit territory, but am not positive.